ACCORDION REPAIR MADE SIMPLE 1

© 2014 George Bachich All rights recerved.Use these links to jump to the accordion repair articles on this page.

ACCORDION REPAIR IS NOT ROCKET SCIENCE

MAKING A BELLOWS PIN PLIERS

OPENING THE ACCORDION

WHY REPLACE OLD LEATHERS?

MAKING A TEST BELLOWS

NEVER OIL YOUR ACCORDION

REED VALVES - PLASTIC OR LEATHER?

POLISHING YOUR ACCORDION

PROPER SHOULDER STRAP LENGTHS

DOES YOUR ACCORDION NEED TO BE RE-WAXED?

WHEN IS IT TIME FOR A NEW BELLOWS?

WHEN IS IT TIME TO RE-VALVE THE TREBLE SIDE?

MAKING TREBLE KEYBOARD BENDING TOOLS

FREEING STICKING KEYS

TROUBLE-SHOOTING SILENT REEDS

VOICING REEDS

PIANO ACCORDION TROUBLE-SHOOTING GUIDE

CHANGING REED LEATHERS

FINDING AIR LEAKS

THE SUPERSTAR ACCORDION LEAK DETECTOR

REPAIRING STRIPPED-OUT WOOD SCREWS

REPLACING A BELLOWS GASKET

REPAIRING CRACKED OR BROKEN WOOD

INSTALLING A BACK PAD

Questions? Comments? Contact me via email.

In fact, accordions are very low tech. You don’t need fancy tools or expensive electronic instruments to fix your accordion. A sophisticated super-accurate electronic tuner, once a $300 to $500 item, can now be had for just a few dollars at the iPad/iPhone App Store, assuming you already have an iPad or iPhone (download "n-Track Tuner Pro").

But you don't even need that for most repairs. Nearly everything you will need to do can be done with standard tools you can get at the hardware store and a few special tools you can easily make from steel or aluminum rods or in some cases, from hardwood. If you have a hack saw, a bench vise, a bench grinder, a small drill press, a belt sander, and a couple of files, you can make all the special tools you need. The articles posted here on how to make specific types of repairs also include instructions on how to make the required tools.

The most important things you need to repair your accordion are motivation, mechanical aptitude, some hand tools, a work table, a little coaching from someone with experience (like me), and good sources for the correct repair materials. Mechanical aptitude is really nothing more than the desire to fix things, the ability to remember or record how they came apart, common sense, and perseverance.

The hand tools you need for simple repairs are pretty basic. To get any accordion apart and the reed blocks out, all you need are a screw driver and a pair of pliers (the best kind is a bellows pin pliers that you can make yourself from an inexpensive end-cutter pliers - see the short article below). For the most common repair, changing reed leathers, you will find a normally closed tweezers (the kind you have to squeeze to open) indispensable. You will also need a razor to cut reed leathers to the proper length.

Your work table should be big enough to allow you to spread out the three major components of the accordion (treble cabinet, bass cabinet, and bellows) and still have room to work on a reed block or two. Good lighting is essential, and an LED headlight (that straps onto your forehead) is essential for looking into tight places. Your work table should also include a tuning bellows, which you can easily make from an old accordion bellows. See the article on making a test bellows.

To return to the table of contents, click here.

Modify a pair of cheap end-cutters (pliers with the cutting jaws across the end, rather than along one side) by filing two round holes centered where the two cutting jaws meet. The pliers can be cheap imports because you are ruining the cutting edges anyway. Make one hole about 3/16" in diameter for large bass pins, and make one 3/32" in diameter for small pins. I used round files of each size chucked into my drill press, and squeezed the pliers onto the spinning file until I had the hole I wanted. Here is a photo of the pliers I made.

To return to the table of contents, click here.

It is best to remove the shoulder straps and the back pad (if any) before opening the accordion. Once that is done, locate and count the bellows pins on the treble side of the bellows. There will usually be three or four on the back and three or four on the front, but there may also be one on the top and one on the bottom. Avoid marring the pins or the plastic finish on the accordion when you pull the pins. If you don't have the special pliers made for this purpose, you can wrap the jaws of any pliers with tape to pad them.

Stand the accordion on its feet, that is, with the bass plate and bass strap down. Grip each treble side bellows pin with the pliers and pull it straight out, steadying the accordion with your other hand as you do so. Some accordions have screws in place of the pins, in which case you will spin them out with a screwdriver. Keep the screws and/or pins in order, as they are often not all exactly the same length or diameter, and they should be put back into the same holes they came from. (To keep them in order, I stab them into a styrofoam block in the same order in which they are to be reinstalled, front pins in the front of the block, rear pins in the rear.)

When you have removed all the pins from the treble side of the bellows, try lifting one corner of the treble section off the bellows. You may have to hold the bellows down while you pull up on the treble section. If you meet significant resistance, check for any bellows strap or snap mounting screws within a half inch of the bellows that might be penetrating the bellows frame and remove them also. Forcing the accordion apart while any screw or pin still penetrates the bellows frame can damage the bellows frame, necessitating a costly repair.

In lieu of bellows pins, some aluminum bodied Hohner accordions have two lever latches under the treble grille that release the treble side from the bellows. On those models, remove the grille, rotate the levers 180 degrees, and lift the front of the treble cabinet off the bellows, then disengage the hinge clips at the back. Do not remove the screws along the back. To separate the bellows from the bass side of these accordions, first remove the bass cover, then release the two thumb clips and remove the bass machine and bass button board as an assembly, and finally, remove the five screws that fasten the bass cabinet to the bellows. The bass cabinet can the be lifted free of the bellows.

When the treble section first separates from the bellows, peek inside to see if any internal microphone wires must be disconnected before lifting it far enough to tear those wires loose from their mounting, which is often very fragile. Once the wires are unplugged, turn the treble section over and set it on the table with the reed blocks facing upward. Now you can inspect for bad leathers, cracked wax, missing reeds, loose reed blocks, etc.

If your accordion has no tone chamber, the treble side will look something like this:

If it has a tone chamber, it will look like this:

The bass side, with the bellows attached, looks like this:

For better access to the bass reed blocks, remove the bellows from the bass section as well, but not before noting how it goes back together. If there are four bellows pins on the front of the bass section and three on the back, then it will be obvious which way the bellows goes back on. If it is not obvious, then mark the bellows frame with a pencil so you can be sure to put it back in the correct orientation, or the bellows frame will not seal and your bellows pins will not line up. Be sure to unplug any microphone wires before lifting the bellows too far.

If you are removing reed blocks, be very careful not to bend the register slides. In many older accordions, the slides are mounted in the reed block rather than in the foundation plate. If this is the case, lifting the reed block without first disengaging the slide from the switch mechanism can cause the slide to kink, rendering it useless. Once bent, they are very difficult or impossible to straighten well enough to work properly.

Note the orientation of the reed blocks and the details of the slide’s connection to the linkage so you will be able to put it back exactly the way it came out. When reinstalling any reed block, make sure it is securely and rigidly fastened down so no air can leak under it.

When you have finished your interior inspection, set the bellows back onto the bass section (being careful not to snag any bass reed leathers in the process), reconnecting any microphone wires as you go, and install the bass side bellows pins. Then set the treble section in place on the bellows, reconnecting any microphone wires as you go and making sure you have the bass buttons and treble keys all facing forward.

Install the bellows pins in their proper holes. If the pins are hard to push in, you can save wear and tear on your fingers by pushing them in with a small block of wood. However, if you have to push very hard, you may have the wrong pin in the wrong hole, or something misaligned. Make sure you have the best fit for all pins before forcing any pin into any hole. Finally, reinstall any bellows strap screws you may have removed, and put on the shoulder straps and back pad.

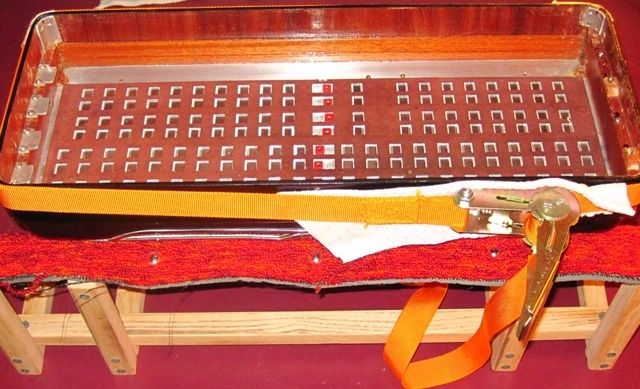

Access to the bass machine is easiest while the treble side is removed from the bellows, because this allows you to set the bass half of the accordion down on its bellows with the bass cover facing up. If you don’t take the treble side off, it is hard to stabilize the accordion in this position unless you use an accordion stand, a simple frame that keeps the accordion from tipping over or sliding away while you remove the bass cover. You can make it out of scrap lumber and a few drywall screws. I used 1 x 1 boards I ripped from some recycled 1 x 4, but you can make yours from just about anything. You might want to pad it with felt, foam rubber, or carpet to help protect the finish on your accordion.

Usually, you remove the bass strap by backing off the large knurled nut until that end of the strap comes loose. Many really old accordions have the strap screwed directly to the bass cabinet, in which case you simply remove the screws. Others have a pair of machine screws mounted in the bass cabinet (threaded ends facing upward) that engage holes in the bass strap. In this case, a rectangular washer and small knurled nuts on those machine screws clamp the strap in place, so just remove the nuts and washer. It is usually not necessary to disconnect the other end of the bass strap. Just pull the strap out of your way to get access to the bass cover fasteners. The bass cover is usually held on by four screws near the corners, but sometimes just two screws, top and bottom, and sometimes with some sort of spring clips or sliding pins or push-button releases, and no screws at all. Watch out for very tiny countersunk wood screws along the edges of the bass cover, especially near the center of the front edge. If there are any, you definitely want to remove them before pulling the bass cover off. Once you have the cover off, you can see the bass machine. When you put the bass cover back on, be sure to guide the air release button through its hole in the bass cover before you install any of the screws.

Here is a typical bass machine:

To return to the table of contents, click here.

WHY REPLACE OLD LEATHERS?

Proper accordion maintenance includes periodically checking the reed leathers and replacing any not in perfect shape. What is perfect shape, you say? Well, every leather should be soft and pliable and should return to position tight against the reed plate after each use.

Reed leathers are small leather check valves mounted on the reed plates. There are two on each reed plate - one on the side facing into the reed block and one on the side facing outward, that is, out into the bellows. Their function is to prevent bellows air from leaking through the reed vents (slots over which the reed tongues are mounted) not in use. Leathers should close under their own power whenever they are not forced open by air coming through the reed vent behind them.

When the bellows is expanding (bass section moving outward), the reed tongues on the inside of the reed block are in use, as air is drawn into the accordion through any open note valves. The leathers on the inside of the reed block adjacent to those reed tongues close off the adjacent reed vents to prevent air from leaking into the bellows through those vents and through the reed tongues behind them on the outside of the reed block.

When the bellows is being compressed (bass section traveling inward), the air flow is reversed, bringing the reed tongues on the outside face of the reed block into play. In this case the leathers on the outside of the reed block remain closed to prevent air from leaking out past the reed tongues on the inside of the reed block. Air rushing out of the accordion through any open note valves forces the interior leathers on those particular reeds to open, while the higher pressure within the compressing bellows forcefully closes the leathers on the outside of the reed block.

If leathers hang open too far, say 1/4 inch or more, they may not close at all, resulting in a significant air leak, and throwing the adjacent reed tongues out of tune. This can make you think your accordion needs tuning, but simply replacing the bad leathers will probably bring it back into tune.

If leathers hang open between 1/4 and 1/8 inch, they may eventually close, but only after their adjacent reeds have begun to sound. Those reeds will initially sound out of tune until their leathers close, at which time they will suddenly jump back into tune, resulting in an audible pitch change shortly after the reed begins to sound.

Leathers hanging just slightly open, say 1/8 inch or less, will be forced closed by air pressure before the adjacent reeds begin to sound, but not before some air has leaked through the vents they are supposed to seal. This leaking air momentarily relieves the pressure on the adjacent reed tongues, slightly delaying their response. Even though these marginally bad reed leathers may not sound bad, they will sap your accordion's performance, causing your reeds to respond more slowly and causing the accordion to use more air than necessary.

To get the best performance out of your accordion, you should keep all the leathers in perfect shape. Some people pay thousands of dollars extra for accordions with handmade reeds because handmade reeds respond just a bit more quickly at low bellows pressures, significantly improving accordion performance. You may be able to get a similar increase in performance for much less money simply by replacing all your bad leathers.

To return to the table of contents, click here.

HOW TO MAKE A TEST BELLOWS

You can make a simple test bellows from an old accordion bellows and two pieces of plank or plywood. If the bellows frame has already been cut off your old bellows, as would be the case if this bellows had been replaced by a new one, simply cut two pieces of 1/2 inch plywood to fit over each open end of the bellows and glue them on. Make sure your glue joints are air tight. To facilitate anchoring it to your work bench with screws, bolts, or clamps, make these wooden end caps slightly larger than the outside dimensions of the bellows. A one inch margin all around should be sufficient.

If your bellows still has its wooden bellows frame attached, as would be the case if the bellows had simply been salvaged from a junk accordion, you can use wood screws to attach your end plates to the bellows frames, then seal the joints with hot reed wax. Alternatively, you can put foam weatherstripping or gasket material between the bellows frame and the end plate before screwing it together. This latter solution makes the most sense if you are going to put weights inside.

If you prefer not to anchor the bottom end plate to your work table, you can add enough weight inside to hold it down while you are lifting the top plate to expand the bellows. A couple of bricks or a big box of bolts or a bag of sand placed inside the bellows should do the trick.

Make a hole near the center of the top plate approximately the same size as the holes in the bottoms of each chamber in a reed block, about 1/2 inch in diameter. A hole this size will minimize the need to silence adjacent reeds in order to hear just the one you want to test, and is best if you will be using your test bellows just to check the operation of reeds and leathers.

However, if you will be tuning, it is essential that the hole in the bottom of the reed block be consistently placed completely over the hole in the top of the test bellows. In that case, a larger, rectangular hole is best. The hole on my tuning bellows (not the one shown below) is 7/16" wide (parallel to the rail) x 3/4" long. The drawback to larger holes is that air sometimes feeds to multiple reeds, forcing you to silence all but the one you want to test.

Glue a piece of leather to the top plate, fuzzy side up, centered around this hole. You might also choose to fasten a small wooden rail or metal angle about 1/4 inch away from the hole to facilitate properly aligning the reed block over the hole. If you have made a larger rectangular hole, you can place the rail a bit closer, say 1/8" from the hole. If you scribe index marks on the rail aligned with the edges of the hole, it will be easy to see whether you have it centered.

To use the test bellows, place the reed block on the top plate with the hole on the bottom of the reed chamber of the reed you wish to sound aligned with the hole in the top plate. If the hole in the top plate is large enough to also sound the reed on the opposite side of the reed block, you can silence it with a piece of fabric or leather squeezed against it with the fingers of the hand holding the reed block in position. Your other hand will be used to raise and lower one end of the test bellows to force air over the selected reed.

When using your test bellows for tuning, be aware that the pressures are reversed relative to those inside the accordion. Compressing the test bellows generates higher pressure air to drive the reed tongue on the inside of the reed block, while on the accordion, the higher pressure air resulting from bellows compression drives the reed tongue on the outside of he reed block. Thus, on the test bellows the inner reed tongue works under higher pressure than the outer one, just the opposite of what occurs inside the accordion. Since the reed frequency is impacted by air density, which is proportional to the pressure, the frequency of both the interior and exterior reeds will be different on the test bellows than they are inside the accordion. Tuning the reeds to their proper frequencies on the test bellows will throw them out of tune in the accordion, where it really matters. The proper use of a test bellows during tuning is therefore limited to making corrections of the magnitude determined while the reed block is in the accordion. That is, if the reed plays three cents too flat in the accordion, you can use the test bellows to determine when you have sharpened it the required three cents. For instance, if on the test bellows the tuner indicates that same reed tongue is one cent too sharp, you can sharpen it until it indicates four cents too sharp, which should put it right on pitch once it is back in the accordion.

Your test bellows has many uses other than tuning. You can use it to voice reeds, to find loose reeds, to find silent reeds or to verify that you have successfully cleared them, to observe reed valve (leather) operation, and, in conjunction with your tuner (or your well trained ear) to sound possible replacement reeds to determine whether they produce the note you need.

Here are two photos of one I made recently. I used an old bellows cut from an accordion to allow installation of a new bellows, so the old bellows had no frames on it. I glued the bottom of the bellows directly to the bottom board, made a new bellows frame from 1 x 1 lumber, which I glued to the top of the bellows, and screwed the top board to that bellows frame with foam rubber weatherstriping sandwiched in between as an air seal. Because I did not want to screw it down to my work bench, I put a bunch of heavy bolts inside, glued in place to keep them from shifting around, These can also be made without interior weights and mounted under a table, actuated downward by foot pedals and returned upward by springs, but I prefer to have mine on top so I can operate it by hand in order to feel the pressure being applied and get a better sense of how the reed is responding to that pressure.

You can use your imagination to build a different design. One of the readers of this website, Chris Krasev of Milton, Ontario, submitted the following photo of an interesting one he built. As you can see, he added moveable rails and air valves made up from register slides salvaged from a junk accordion.

Dennis Amott of North Vancouver, Canada, sent me a link to his Youtube video of a tuning bellows he made. If you click the link, you will see that he made a portable table top model that opens downward, so the top plate remains stationary and level as the bellows is opened, allowing it to be operated with just one hand.

To return to the table of contents, click here

Accordions are big air filters. Lots of air is pumped through them, and the moisture, dust and lint in the air all tend to collect on interior parts, so the air emerges cleaner than it went in. This accumulation of lint in the accordion is inevitable, but oiling any part in the accordion tends to make it even worse. The oil attracts more dust and lint than before, and when enough of it combines with the oil, it makes a thick, gooey substance that can cause keys, bass buttons, and register switches and slides to stick.

When you encounter a sticking key, button, switch, or slide, you may be tempted to oil it, but on accordions you should resist that temptation. The better course is to take it apart, clean it thoroughly, determine the source of friction, sand, smooth, polish, realign, or loosen parts as necessary to reduce the friction, and put it back together dry. Although oil may seem to help in the short run, in the long run you will regret using it. If you absolutely must use some lubricant, try graphite, but very sparingly, or you will have another kind of mess as the graphite spreads to areas you never intended it to go.

To return to the table of contents, click here

REED VALVES - PLASTIC, OR LEATHER?

Some accordions are now made with plastic reed valves (ventilli) rather than the more traditional leather. Is this an improvement in accordion quality and performance, or just a cheaper way to build an accordion?

Plastic reed valves have some apparent advantages. They are lighter and more flexible, and therefore may open under less bellows pressure. If this were to allow the reed to respond more quickly, it would improve accordion performance. After all, rapid reed response is one of the highly desirable characteristics of reeds. But if the amount of air flow required to open the leather reed valve is already less than that required to sound the reed, then a valve that opens even earlier would offer no real advantage.

Previous observations lead me to predict that if the plastic ventilli do offer any advantage, it will be most apparent at the higher frequency reeds. These are the smallest reeds in the accordion, which require the least air flow to sound, and which do not normally have leathers because the air flow required to sound the reed is not sufficient to force a leather valve open. Installing a leather on these small reeds significantly delays their response or silences them entirely. It is here that the plastic ventilli, if it actually opens under less pressure, would be most helpful. But it is also here that leathers are least needed, because the leakage around these tiny reeds is already very limited by their size. I therefore suspect that although plastic ventilli probably do offer some performance advantage at the higher notes, and especially on handmade reeds which require even less air to operate, the advantage is likely to be small.

Plastic ventilli offer another apparent advantage. The plastic seems much less likely than leather to curl away from the reed plate, because plastic is lighter and less likely to sag, and because it is impermeable to moisture, which is reputed to be one of the major contributors to the curling of leather.

However, plastic cannot duplicate one of the reputed functions of leather, which is to help keep the reeds dry by absorbing moisture from the air. The importance of this function is a matter for debate, and the question is moot in cases where the accordion is not subjected to moisture. Nevertheless, leather reed valves might have an advantage on this point.

Plastic ventilli are available in more distinct lengths than leather reed valves, and thus offer time savings during installation by eliminating the need to field cut leathers to the proper length for each reed. They are also less expensive than leather, although leather reed valves cost only about ten cents each in large quantities, amounting to about $35 for a full set for a full size 41/120 4/5 accordion.

So which should we use? Until I or someone else experimentally confirms that plastic noticeably improves reed performance, I will continue replacing leather with leather and plastic with plastic unless I feel the leather might be adversely impacting the response of a particular reed, in which case I will substitute a plastic ventillo.

To return to the table of contents, click here

POLISHING YOUR ACCORDION

Accordion manufacturers polish the celluloid finish on their accordions using large floor mounted buffing wheels and a series of successively finer abrasive buffing compounds.They do this polishing prior to attachment of grilles, straps, metal trim, etc, and before the accordion is assembled. At the polishing stage, the treble and bass cabinets are devoid of keys, buttons, reed blocks, and bellows. The operator stands in front of the rotating cloth buffing wheel, applies buffing compound to the wheel, then presses the bare accordion cabinet into it, being careful not to generate enough heat to cloud the surface of the celluloid. When he has it uniformly shiny, he switches to a different buffing wheel where a liquid polish is used for the final finish.

Although few of us have large buffing wheels at our disposal, we should adopt this general approach whenever we polish our accordion, even if we polish by hand. That is, the accordion should be disassembled and the individual components polished separately. In this way we avoid leaving unsightly deposits of buffing compound under the edges of metal trim parts, at the junction of treble grille and treble cabinet, on the grille cloth at grille openings, and in between keys and buttons. This approach also allows us to polish what would otherwise be difficult to reach corners where cabinet and trim parts meet. Using buffing compound and a powered buffing wheel saves time and effort, but even fairly significant marring of the finish can be polished out by hand if you apply buffing compound in sequentially finer grades along with a lot of "elbow grease". For the final finish, use the micro-abrasive polishing compounds sold in auto parts stores specifically for restoring the clarity of plastic automobile head lamp lenses. Don't use so much that it flows over the surface or into little nooks and crannies where you can't get it all out.

In between these major polishings, we need only wipe off the finish with a soft cloth. If the finish is really grungy, the cloth can be dampened with rubbing alcohol, but no liquid should ever be poured or sprayed onto or into your accordion. Slathering wax all over your accordion, then buffing it out like you would your car just makes a mess, due to all the angles, joints, and other irregularities in the surface. Besides, mechanically polished celluloid is naturally shiny, and does not require wax. If the finish has dulled, wax will not improve it much anyway. The marring and scratches should be mechanically buffed out just as they originally were at the factory.

Special care should be taken with the keyboard. Keys can be cleaned in place using a soft cloth dampened with rubbing alcohol. But never allow any liquid to run down in between the keys. The keys and keyboard are usually made of unfinished wood. Moisture absorbed into the wood can cause local swelling and warping, which in turn can cause keys to stick. For particularly difficult key cleaning jobs, see the article on cleaning and buffing keys.

The real key to keeping your accordion shiny is not to let it get dirty in the first place. If you protect it from scratches and wipe it off with a soft dry cloth or chamois each time you play, it may never need to be polished.

To return to the table of contents, click here

Accordion shoulder straps come in mismatched pairs, that is, one strap is longer than the other. If you examine them closely, you will see that the upper portion of each is identical, and all the variation is in the tail, which connects to the bottom of the accordion. The strap on the right has the longer tail because the accordion must sit left of your center. Depending on your size and the location of the strap brackets on the accordion, the right shoulder strap might be 4 to 6 inches longer than the left when properly adjusted.

When adjusting your straps, you should begin with the left one and adjust it short enough to hold the accordion suspended from your left shoulder so that the centers of the black keys on the right side of the accordion are directly under your chin, and the top of the accordion is about four inches below your chin. Then adjust the right strap long enough to accommodate the accordion position achieved with the left strap alone.

Many accordions have straps too long to be adjusted in this manner. In that case, you might be able to punch more holes in either or both ends of the strap segments to allow them to be shortened by adjusting the buckles. But if this still will not allow the straps to be adjusted tightly enough, you will have no choice but to shorten them. In this case I generally switch the tails so the shorter tail goes with the right strap, so I only have to shorten one of them. In other words, the short tail becomes the long tail and the long tail gets shortened to become the new short tail, usually 4 to 6 inches shorter than the other.

Begin by drilling out or prying apart the rivets that hold the large buckle in place. Note the location and size of the slot for the tongue of the buckle and the location and spacing of the rivet holes, and duplicate that pattern farther down the strap at a location that will produce a tail of the desired length. If you wish, you can cut off the excess strap length and use it as a template to make the new holes. Use new two-part rivets to install the buckle in the new location, in the same manner as it was originally installed.

If you plan the tail lengths to fit when each tail's buckle tongue is in the middle hole of its upper strap, you will have ample room to make minor adjustments in either direction later.

To return to the table of contents, click here

DOES YOUR ACCORDION NEED TO BE RE-WAXED?

The hundreds of aluminum reed plates in your accordion are held to the wooden reed blocks by a mixture of beeswax, resin, and a small amount of linseed oil. Over time this mixture dries, hardens, and becomes brittle. Eventually, it will crack around the reed plates, allowing them to vibrate themselves loose. When your reeds start falling out, it is definitely time to re-wax.

However, you might decide to re-wax before reeds start falling out. For instance, if your accordion needs tuning, the reeds should be thoroughly cleaned before tuning begins. This is because the dirt on them is probably what causes them to be out of tune. If you tune a dirty reed, then clean it later, it will need to be tuned again. You can short-cut by using a tiny brass wire brush to clean the outside of each reed tongue, but it is practically impossible to clean the side facing into the reed block. The only way to thoroughly clean them is to take them out of the reed blocks first. This naturally requires waxing them back in after they are cleaned. If very many reeds need tuning, you might as well re-wax the whole thing.

There are other reasons to re-wax. The quality of the sound your accordion produces is partially dependent on the condition of the wax. This is because the reed itself produces only a feeble sound until it is anchored to a reed plate and until that reed plate is anchored into a reed block, which in turn is mounted to an accordion. The vibrations of the reed tongue are transmitted through the rivet to the reed plate, then through the wax to the reed block, then through the wooden reed block and on into the accordion cabinet. That's why you can feel the accordion vibrating against your chest as you play it. The accordion cabinet is a bit like the sound board in a piano, or the body of an acoustic guitar. The quality of the sound we hear depends on the efficiency with which those vibrations are transmitted through the various materials, including the wax, as well as on the quality and construction of the reeds and cabinet. Old brittle wax transmits sound differently. Fresh wax could make your accordion sound more like it did when it was new.

However, re-waxing is very time consuming and expensive. If you pay to have it done, the cost could exceed the market value of your accordion. In this case you might decide to forego the new wax and just spot tune the reeds needing it most. You might also decide to wax it yourself, in which case you might be interested in the article on waxing reeds to be posted soon on Accordion Repair 2 of this website.

To return to the table of contents, click here

If an accordion uses very little air, we often describe it as having a good, tight bellows. If it uses lots of air, we sometimes say it has a leaky bellows. But often the leaks are actually elsewhere, in which case replacing the bellows will not solve the problem. How can we know if our bellows should be replaced?

Some people replace their bellows just to get a different color. But a new bellows installed can cost $350 to $450. At these costs, you probably prefer not to replace your bellows unless it is truly necessary.

The first step is to determine exactly what is leaking. A good article on how to analyze and locate your air leaks is posted elsewhere on this page. Following the procedures outlined there should help you find and fix your leaks, and may save you the expense of a new bellows. If you find the bellows leaking, you may want to replace it, as bellows repair is time consuming and costly, and often leaves the bellows looking a bit rough. However, it still may be economical to repair your old bellows if you do it yourself.

If you have eliminated all other possible sources, and if you know your leak is an external leak as defined in the "finding leaks" article, you may conclude that your bellows probably has lots of small leaks, each too small to detect, that add up to a lot of lost air. In that case, replacing your bellows will probably breathe new life into your accordion and be well worth the cost.

You might also decide to replace your bellows if it has more than two or three loose metal corners. A few corners can be replaced fairly economically (especially if you don't mind leaving the bellows tape in a bit of a mess right at the corners), but replacing them all costs about as much as a new bellows, especially if the bellows is re-taped at the same time. If just a few corners have come loose because the glue has failed, it may make sense to repair it. But if the corners are loose because the metal has cracked, then many other corners are also likely to be cracked and will work loose shortly, in which case you will be better off with a new bellows.

You might also consider a new bellows if most of your bellows tape needs replacing, as the labor cost of re-taping an entire bellows could exceed half the cost of a new bellows. The advantages of having a new bellows might outweigh the savings realized from replacing just the tape. These advantages include a long trouble-free service life, a newer appearance, improved air tightness, improved stability, and the opportunity to pick a new color.

Improved stability is a factor worth mentioning. Sometimes, even when they don't leak, old bellows just get so loose and flexible that they tend to bulge out of alignment under compression, requiring you to follow them around a bit in order to push them closed. If your bellows starts acting more like a Slinky than a bellows, you might be happier with a new one.

You will find two bellows-related articles on the "Accordion Repair 2" page of this website - "Replacing Bellows Tape", and "Installing a New Bellows". In the future you will also find an article on general bellows repairs.

To return to the table of contents, click here

IS IT TIME TO REVALVE THE TREBLE SIDE?

If you find leaks at the treble valves, you might be able to adjust the pallets to stop the leak. Check first to see that the offending pallets are centered over their ports and that all four corners as well as the centers of each side of each pallet are in firm contact with the foundation plate, and adjust them as necessary for a good seal by bending the key rods.

To check for firm contact, cut a narrow strip of paper to use as a feeler gauge under the valve to be sure you have equal drag on all four corners and along each side. See the discussion on leveling the keyboard in the article titled “Setting Up a Treble Keyboard for Shallow Action” for some useful tips on how to bend the key rods without damaging the keys or pallets, and for instructions on how to make the tools you need. Also make sure no debris is lodged under the pallet that might prevent a good seal.

If you find all four corners snug, but poor contact along the middle of one or both sides, then you probably have a warped pallet, in which case you will have to remove the pallet, strip off the valve facing, sand the pallet flat, and install new valve facing.

If the pallet seems to have firm contact all around, yet still leaks, then remove the key, fluff up the nap of the leather valve facing with a tooth brush, and reinstall it (see the discussion on how to disassemble various kinds of keyboards in the article titled “Setting Up a Treble Keyboard for Shallow Action”).

If the leak persists after all this, it is probably because the surface of the valve is pillowed due to compression of the felt liner. It is normal for the nap of the leather to be flattened around the port, leaving a visual image of the ports in the leather facing, but if you can also feel a raised waffle pattern left by the ports, then it may be time to re-valve.

This pillowy waffle pattern is caused by compression of the felt under the leather valve facing due to age and normal wear. Whenever you see noticeable pillowing, you will be better off to re-valve, because the new valves will seal better and will also operate more quietly. If such a valve is off center and you try to center it, the waffle pattern will no longer fit exactly into the ports, and the valve will still leak. The only solution in this case is to replace the valve facing with new leather/felt laminate. If one valve is pillowed, all the others are probably also pillowed, in which case it is time to re-valve the treble side of the accordion. The bass valves normally have thinner felt pads which are much less prone to pillowing.

You might decide to re-valve even if no valves are leaking. If any of your treble keys are higher than the ends of the keyboard cabinet, this is usually evidence of valve felt compression. Place a long straightedge lengthwise down the keyboard, extending past the keys at both ends of the keyboard. When the accordion left the factory, all the keys were probably level with the ends of the keyboard. The extent to which you can depress keys with this straightedge is the extent to which compression of your treble valve facings has allowed the keys to rise.

Compressed felt is less effective as a cushion, resulting in more noise when the valve slams shut under the pressure of its return spring. The compressed felt also allows the key to return to a higher position, thus lengthening the key stroke and giving the spring more time to accelerate the valve, giving it more momentum to dissipate upon closing. Most of this momentum is dissipated as noise. Leveling the keyboard can eliminate this extra travel and the resulting extra momentum, but it does nothing to make the felt a more effective cushion. If you have a clunky noisy keyboard, re-valving is the best way to improve it.

See the article titled "Renewing Treble Valves" for tips on how to do it, where to get the felt and leather laminate, and other options for improving and quieting your keyboard action.

To return to the table of contents, click here

You sometimes need to raise or lower treble keys, either to correct one that has been bent upward by catching on a case or strap, or to compensate for different rates of deterioration and compression of the felt valve padding, or to compensate for a slightly different thickness of valve facing material used to re-valve, or to set up the keyboard for shallower action. Raising or lowering treble keys is accomplished by bending the key rods.

But let's start with how not to bend key rods, as some people are tempted to try shortcuts, which seldom work out as desired. For instance, do not hold the key down while you press down on the treble pallet, and do not simply pull up on a key to raise it. Either of these actions will compress the felt valve padding, perhaps producing the desired result temporarily, but only until the felt lofts again to near its original thickness over the next few hours. Using this "shortcut" could also loosen the treble pallet's connection to the key rod, which is often just a bed of wax. If your "shortcut" over-stresses the key's hinge point on wooden keyboards, you may crack the key or the wooden boss on the keyboard cabinet that holds the spindle. On older accordions with the key rod driven into the wooden key like a nail, you also risk loosening the key rod's connection to the key, necessitating a time- consuming repair.

The correct way to bend key rods is with two bending tools, one gripping the rod on each side of the point where you want to make the bend. For raising or lowering the key, place the bend as close as possible to the key. If this puts the pallet out of parallel with the foundation plate, causing the valve to leak, then make the compensating bend as close as possible to the pallet. All this is explained in more detail in the article on setting up a treble keyboard. The main thrust of this article is to describe the bending tools and how to make them.

The simplest tool is a steel rod with a slot cut in one side of it just the right depth and width to grip the key rod. The problem is that key rods come in many sizes, creating the need for many tools unless you make a set of adjustable tools. We'll get to a couple of designs for adjustable tools shortly, but first let's cover the simple ones. If you are only working on one accordion, then a few simple tools may be all you need. Here is a photo of some of the non-adjustable bending tools I have made from steel rods and bolts. The narrower tools are essential for working on short key rods.

The first and second tools from the right, with large grip handles and with slots in the end, are for bending the key rod side to side in order to center the pallet over its ports. The fourth and fifth from the right are for twisting the flatbar style of key rod in order to rock its pallet into parallel with the foundation plate. Note that in each case pairs of tools are used together. The third tool from the right has small pegs through it to engage the key rod, and is useful (in conjunction with one of the other tools) for putting bends very close to the pallet. Here is a close up photo of it.

Adjusting valves down inside a tone chamber requires special tools that reach down into the chamber. The seventh and eighth tools from the right in the top photo have worked well on some tone chamber accordions, but I expect to have to make different tools with different slot widths to fit other accordions which have different key rod widths.

My tool design is still evolving, and I expect it will continue to improve. If you come up with any better tool design ideas, I hope you will share them with me.

When designing your bending tools, keep four considerations in mind. The first is that the tool must be narrow enough to fit down between adjacent key rods. This dimension varies with different accordions, but bulky tools just won't fit. The second is that wider tools with longer slots to grip the key rod do less damage to the soft aluminum key rods (very narrow tools cause unsightly gouges in the aluminum). The third consideration is that for the short key rods on the black keys, wider tools are not practical, since they do not allow you to put one bend close to the key and another bend close to the pallet. Tools wide enough to preclude any damage to the key rod are also wide enough to occupy the entire length of a short key rod when used in pairs, eliminating any choice on where to place the bend. For your black keys, you will therefore need narrow tools and you will have to live with the divots they leave in the key rods. The fourth consideration is that when raising a key, you will have to move the tools toward each other, and their handles may need to bypass each other in order to make the desired bend, so slender handles work best.

You can help minimize key rod damage by making your narrower tools from square rod, rather than round. For any given tool width, this maximizes the contact surface between the tool and the key rod, thus spreading the load. You can also minimize the damage by making the slots just barely wide enough to receive the key rod. A tight fit helps maximize the contact surface between the tool and the key rod, spreading the load over a wider area, thus minimizing the damage.

Making your bending tools about six inches long will give you sufficient leverage to bend the key rods. Minimizing the amount of rod extending beyond the lower edge of the slot will help make the tool fit closer to the pallet, making it possible to get your two bend points farther apart, which is particularly important on the black keys and any white keys with short key rods.

Here is a photo of some adjustable bending tools I have recently made. The one on the right has a slot in the lower jaw to straddle the key rod extending down into a tone chamber.

In the next photo the three on the right above have been disassembled so you can see how they are made. The set screw threads into one half of the tool and rides in a slot in the other half of the tool. The one in the middle has an adjustable slot on each end. The two halves of that tool were made to different lengths to provide different adjustment ranges at each end of the tool. The three extra holes in the tool on the right are unnecessary. They were already in the angle before I converted it to this use.

The adjustment, of course, is to allow for gripping a wide variety of key rods of varying thicknesses. I made the tool on the left from some recycled cold formed slotted channel (originally used to mount adjustable shelf brackets to a wall), and from some 1/4" steel plate I cut from a scrap of 4-inch wide 1/4-inch flat bar. To eliminate the need for a bulky nut, I tapped #10-32 threads in the 1/4-inch plate to receive the pan head set screw. When slightly loosened, the set screw can slide in a 3/4-inch long slot cut into the web of the channel. This gives me an adjustment range of 9/16- inch (3/4-inch minus 3/16-inch for the diameter of the #10 machine screw).

I am not a professional tool designer. Although these tools serve their purposes, I am sure more elegant designs are possible, and I encourage you to experiment. If you care to share your improved design, I would love to know about it. - GB

To return to the table of contents, click here

Treble keys sometimes stick open due to dirt or corrosion on the key or the spindle (axle rod), due to warping of wooden keys, or due to bending of aluminum keys.

Repairing a key that sticks open requires removing the key, after first removing the grill and possibly the treble switch assembly. On accordions without individually removable keys, pull the spindle out far enough to release the sticking key.

Look for the ends of the spindles (or spindle) under a small metal cover on the bottom of the keyboard. If you remove the spindle or spindles without first securing the keys in place, the key springs will fling the keys off the keyboard one at a time as the spindle is withdrawn, so plan to catch them. If they are not already numbered, number each key as it comes off to facilitate getting them all back in their proper places. The usual numbering system is 1 through 41 starting at the bottom of the keyboard if all keys are on one spindle. If there are two spindles, the black and white keys are numbered separately.

If you prefer not to remove all the keys above the problem key, and if there are two spindles, you can tape the keys together so that one spindle will hold all keys in place, as described in the following paragraph. If there is only one spindle, you can avoid removing all the keys by clamping them in place in accordance with the paragraph after that.

If white and black keys have separate spindles, you can usually avoid removing other keys by taping all the keys (except the keys to be removed) to each other before pulling out the appropriate spindle. (Use 3M Scotch Brand #218 plastic masking tape, as other tapes leave a sticky residue). Place one row of tape near the ends of the white keys and two rows over the black keys, taping to the tops of the white keys and to the sides and tops of the black keys. If you pull out just one spindle, the other spindle and the tape will hold all the taped keys in place.

If there is only one spindle for all the keys, you can clamp in place the keys you do not wish to remove, using large spring clamps with extended jaws to hold rods and shims against the keys. A single clamp can hold a wood ruler or similar shaped plastic or aluminum rod across the ends of the white keys, pressing them all down under the clamp's spring pressure. Two other long-jawed spring clamps (bolt 6-inch wood, plastic, or metal extensions to the jaws) can be used to press another similar rod down onto the white and black keys right where the black keys emerge to the level of the tops of the white keys, i.e., at the key hinge point. Finally, a third rod is used as a shim between the extended clamp jaws and the tops of the black keys to help hold the black keys in place. Just make sure none of the rods or shims extends out over the keys you wish to remove.

Grip the end of the spindle with small vice-grip pliers, and twist while pulling. Pull the spindle out just far enough to release the sticking key. Lift the key out, carefully noting the placement of the key spring. The free end of the spring must point toward the outer end of the key (not toward the valve), and usually rides in a tiny groove in the wood. Note that this technique does not work on a few models in which both spindles pass through holes in each key. In this case both spindles must be at least partially withdrawn in order to remove any key from either spindle.

While you have the spindle partially out, take a close look at it. If it appears dirty or corroded, remove it entirely and clean it with steel wool before reinstalling it. Inspect the key and the keyboard slot for any dirt or lint that could cause the binding, and for shiny spots that indicate where the key is rubbing.

For all-wood keys, sand away the shiny spot, finishing with 600 grit sandpaper. For wooden keys with aluminum core, and for all-aluminum keys, very slightly bend the short aluminum tab on the bottom away from the side where it was rubbing to eliminate interference with the slot in the aluminum keyboard. If this tab appears worn or scratched, you should also smooth it out with fine sandpaper and finish it with steel wool. Another option is to shift the key to one side by slightly bending the key hinge. Keep in mind that a very tiny bend at the hinge point results in a relatively large sideways shift out at the end of the key.

Reinstall the key and its spring and reinstall the spindle, taking care not to bend it. To avoid bending it, remove a drill chuck from a drill motor (or buy a new drill chuck) and slide it onto the rod, tightening it about four inches from the bottom of the keyboard. Use the chuck to twist and push the rod in, then loosen the chuck, slide it back, tighten it, and push again. If the spindle is brass, avoid marring its finish. You may have to press the keys slightly down into proper alignment to allow the spindle to pass through. The end of the spindle is tapered, so you may be able to see the keys move slightly as the point enters the bore and forces the keys to center themselves on the spindle.

If your accordion has a tone chamber, you may find that some of the black key rods intertwine with some of the white key rods in a way that makes it impossible to take out just the black keys or just the white keys. Similarly, you may find that both spindles pass through separate holes in each key. In either of these cases you will have to pull out both spindles and when you put it back together you will have to install black and white keys and both spindles together, and the drill chuck idea will not work because the spindles are too close together.

To solve this problem you can make aluminum, plastic, or hard rubber jaws for your small vise grip pliers that allow you to grip each spindle from the side an inch or so away from where it enters the cabinet without marring the smooth finish on the spindle. Here is one I made by hammering some 1/8" aluminum flat bar around the jaws of an old pair of vice grip pliers. I squeezed those jaws around a file spinning in my drill press to form a rounded groove across each jaw to better grip the spindle.

Here is a keyboard going back together using those pliers.

If there is no cover on the bottom of the keyboard and no access to the bottom ends of your spindles, then the keys are individually removable. Individually removable keys have slots that engage a spindle that can only be removed after all the keys are out.

There are five basic types. The most common type uses a short, stiff retainer spring to hold the spindle in the horizontal leg of an L-shaped slot in the bottom of the key, or more accurately, an L-shaped slot in the brass hinge assembly riveted to the bottom of the key. You cannot see this spring or the slot until you get the key out.

You remove these keys by pressing down hard and toward the valve end of the rod in order to get the spindle out of the horizontal leg of the L-shaped slot (by overcoming the force of the retainer spring) and into the vertical leg, then pulling up on the key to lift it off the spindle. Press on the key right where it rotates on the spindle, pushing down and horizontally, then lift vertically by gripping the key rod as close as possible to the key. In this explanation, horizontal means parallel to the key top.

Once you have your sticking key out, inspect and repair it as above. To reinstall the key, place it back in its slot with the stiff spring against the keyboard side of the spindle and press the key in the direction of the valve to compress the stiff spring in order to allow the spindle to enter the vertical leg of the slot. As you press the key down, the stiff spring will force the spindle into the horizontal leg of the slot to hold the key in place.

A second type of removable key is similar, except they have only a vertical slot (no horizontal leg) and a short coil spring to hold the key in place that must be removed first. With the grille off, you can peak in under the backs of the keys and see these little springs. In these cases, there is often a little tool fastened to the underside of the grille or to the foundation plate under the grille. If not, you can make one from a small screwdriver or any slender steel or aluminum rod. Here are a couple of photos of one I made.

The upper end of the coil spring stays connected to the key; you remove the bottom end of the spring from the aluminum tang by pressing the loop on the end of the coil spring downward and off the free end of the tang. You can remove them with practically anything, but you will need the special tool to put them back on.

There is a third type of removable key that has a simple aluminum fork on the bottom of the key that straddles the axle of a brass bushing that rotates on the spindle. This type always has the little coil springs described above. After removing the spring, you just pull straight up on the key, using a good grip on the key rod. Some of these are really stubborn and you have to pull really hard with pliers. It is not unusual to have to pull so hard that when it finally suddenly releases, you are unable to stop before the pallet hits something and is knocked off the key rod, so you should have some reed wax handy to wax it back on. See the article on waxing with a modified soldering iron for more details. If you don't get it waxed back on in exactly the same position, and if the leather seal has "pillowed" into the ports, it will leak due to the "pillow" no longer aligning properly with the port, in which case the best solution will be to replace the felt/leather laminate valve facing on that pallet. See the article on "re-valving the treble side".

If you have these forked keys and brass bushings, and if you conclude that your problem is high friction between the brass bushing and the spindle or between the brash bushing and its slot in the aluminum chassis, then you will have to take all the keys out and remove the aluminum keyboard chassis from the accordion in order to get the spindle out to clean it. In this case, all the brass bushings will fall out as you remove the spindle, so figure a way to catch them.

You can clean them in a little jar of WD-40, agitating it well, then blow them dry with compressed air. Test each of them on the spindle to make sure they all turn freely. Doing this may help clean additional corrosion and dirt out of the interior bore in the bushing.

As you put them back in their slots in the aluminum chassis one at a time, feeding in the spindle as you go, make sure each one turns absolutely freely on the spindle and in its slot in the aluminum chassis before installing the next one. The bushings vary up to .004 inch in width, and if you happen to get one of the wider ones in one of the narrower slots in the chassis, it may rub on the chassis.

In this case, either find a narrower bushing or file the slot a little wider, but not too wide, or the key may wander too much and interfere with a neighboring key. Every bushing must turn absolutely freely in its slot and on the spindle in order for the keyboard to work smoothly.

If some of the key forks are too tight to fit over the brass bushing with moderate pressure, check the sides of them for burrs or spalling and sand these off smooth. If you conclude that the fork is too narrow, you can file it a bit wider, but don't file too much, or the key will be sloppy. You want a snug fit. Don't use any oil, as it will attract lint and dust, which will eventually gum it up and cause keys to stick.

This type of keyboard takes longer to clean and adjust, but in the end you will be rewarded, because once it is cleaned and properly adjusted, this design offers the smoothest keyboard action of all.

The fourth type of individually removable key is held in place by a sliding clip on each key that slides in under the spindle. Use a flat blade screwdriver to pry the clip away from the spindle (that is, toward the valve end of the key), and lift the key straight up. To replace it, press the key down over the spindle and slide the clip back in.

The fifth type has a slotted head twist-fastener right above the spindle on each key. Use a flat blade screwdriver to turn the slotted head of the fastener 90 degrees left to release the key, then pull the key straight up. To put it back, press the key into position over the spindle and turn the fastener 90 degrees to the right.

In all cases, test the key for smooth action before returning the accordion to service.

To return to the table of contents, click here

TROUBLE-SHOOTING SILENT REEDS

Silent reeds might be missing, loose, misaligned, or broken, but usually they are just stuck because of foreign matter lodged between the reed tongue and the vent (slot in the reed plate). The hardest part is to positively identify which reed tongue is silent. You can always use your tuning bellows to test each reed in each reed block, in each airflow direction, out on the workbench. But there is a quicker way.

First determine which switch controls the problem reed, and in which bellows direction the problem occurs. Then open the accordion and take out the reed blocks to determine which slides are opened by that switch. This tells you which row on the reed block contains your problem reed. Now press the problem key to see which valve opens, and hence, which reed plate in that row contains the silent reed (for example, the fifth valve controls the fifth reed plate in the reed block).

If the reed was silent only when the bellows was expanding (air rushing in), then the problem is with the reed tongue on the inside of the reed block, behind the visible leather. If it was silent only when the bellows was compressing (air rushing out), then the problem is with the reed tongue facing you, on the outside of the reed block.

If it is the outer tongue, you might cure it by simply plucking it lightly with a single edge razor blade slipped carefully under the tip (to avoid scratching either the reed or the reed plate). Pluck it just enough to get it vibrating. If you can hear the tone of the reed at all, you have probably already cleared it. But if it sounds dull, you may need to take further measures to dislodge foreign matter from between the reed tongue and the vent.

Try passing a .0015” metal feeler gauge between the sides of the reed tongue and the vent (slot in the reed plate), but don’t push it in very far, or you will dislodge the leather glued to the opposite side of the reed plate. Then pluck the reed tongue again to see if it seems to be vibrating freely. You can also test it on your tuning bellows if you have one. However, you should avoid blowing the reed like a harmonica, as this could get moisture on the reed, causing it to rust.

If the problem was with the inner tongue, try the feeler gauge approach. You will not be able to pluck the reed to check your progress, but you can test it on your tuning bellows, if you have one.

If passing the feeler gauge around the sides does not clear it, check the tip. The feeler gauge is too wide to use to clean the narrow end of the vent, but you can use it to clean off the tip of the reed tongue and also to lift the reed tip out of the way (not too far, as you do not want to bend it permanently) while you clean the end of the vent with a tiny brass wire brush, or a straight pin, or even a toothpick.

If cleaning fails to solve the problem, then check for misalignment of the reed tongue that causes interference between the reed tongue and the vent. You will probably have to pry the reed plate out of the wax to do this, then wax it back into the reed block after you have repaired it, so if you are not prepared to wax it back in, you should take it to a repairman. If you proceed on your own, hold the reed plate up to a bright light to verify that you have the tongue centered. If the tongue is out of center, pry it back into position. If it moves at all easily, you may have to reset the rivet with a light hammer blow (on an anvil, naturally) after you have the tongue centered.

To return to the table of contents, click here

VOICING REEDS

You can often significantly improve the performance of your accordion by voicing the reeds. Voicing is setting the tip clearance of the reed tongue above the plane of the reed plate. If the tip is set too high, too much air will escape under it, delaying the onset of vibration, requiring more air to get it started. If it is set too low, it will choke under high bellows pressure. That means it will refuse to vibrate, perhaps because it closes off the reed vent too soon, before it has achieved enough velocity and momentum to travel far enough to cause a rebound powerful enough to start the oscillation.

Changing the tip clearance obviously requires permanently bending the reed tongue. You can't voice the reed just by lightly flexing it or by gently stroking it, or it will simply spring back to its original position. If you want it to take a permanent set at a new level relative to the reed plate, then you have to bend it far enough to exceed its elastic limit (which by definition is the bending limit beyond which it will not spring completely back to its original position).

However, you also want the reed tongue to remain straight and parallel with the top of the reed plate or angled slightly up from it, but not having any curvature, so you have to make sure the permanent bend occurs very close to the rivet. You can't just grab it by the tip and push or pull, or the bend might occur somewhere midway along the reed tongue, or perhaps even close to the tip, especially on the smallest reeds.

To get it to yield close to the rivet, you should apply the force at least half way down the tongue. This is where the reed tongue is wider and possibly thicker, and where you have the least leverage, so you have to push or pull pretty hard, and there is the rub. If you push or pull too hard, the permanent deflection may be greater than you want, in which case you will have to bend it back the other way by exceeding the elastic limit again. There is a limit to the number of times you can do this, because each time you exceed the elastic limit, you raise the elastic limit of the steel in the area of the bend so that even more force will be required to exceed the elastic limit at that location next time (this is sometimes called "work hardening" - you can see it in action by repeatedly bending and straightening any steel wire, such as a paper clip).

As the elastic limit increases due to bending beyond the previous elastic limit, by definition the area of the bend becomes more resistant to permanent bending, so the next permanent bend tends to occur somewhere else, where the elastic limit has not yet been raised, and where it will therefore yield under less applied force. In practice, this means that if you want your permanent bend right next to the rivet, you have to get it right the first time, or at least very soon after that. If you exceed the elastic limit very many times, your bend might end up farther away from the rivet. If you somehow force it to bend at the exact same spot each time, then its elastic limit at that point will eventually be raised to the ultimatum yield point, at which point the reed tongue will break, rather than bend.

This is not to say that there is a limit to how many times the reed can flex before it breaks. As far as I know, there is no such limit, as long as it does not flex beyond its elastic limit. Reeds flex millions (or maybe billions) of times during the life of an accordion, so you can try as many times as you like to bend the reed short of reaching its elastic limit, and you will not hurt it, but of course, you won't change its voicing, either.

This all suggests that the best way to voice a reed is with several attempts, starting gently, and gradually increasing the applied force with each trial, checking each time to see if the latest attempt has succeeded in making a permanent bend. There is no penalty for applying too little force, other than a slight delay in reaching your objective. With experience, you will learn how much force to apply the first time, so you can avoid wasting a lot of time working up to the elastic limit, yet still be reasonably certain that you will not exceed the limit on your first try.

I say "reasonably certain" because reeds vary in hardness and in their elastic limits, and even after you have experience, you will undoubtedly encounter some reeds that are much softer and with lower elastic limits than most, and which take a permanent bend much sooner (and farther) than you expect. When this happens, you should reduce the force you use in subsequent trials, and try to work gradually up to the lower elastic limit of that particular reed.

The tools used in voicing are very simple. For lifting an exterior reed tongue to increase its tip clearance, you just need a thin piece of metal to get behind the reed tongue and evenly support the upper half to two thirds of it while you bend it upward. I use a dull single edge razor blade on small reeds, and a .010" metal feeler gauge on larger reeds.

For lowering an exterior reed tongue to decrease its tip clearance, you apply force in the lower half of the tongue, forcing it down into the vent. I use a flat blade screwdriver with a tip narrow enough to pass through the vent without scratching the sides. To avoid letting the screwdriver slip toward the tip of the reed tongue, I hold the screwdriver shank nearly parallel to the reed and rock the tip into the tongue, rather than poking it straight in.

If you are voicing an interior reed tongue on a reed mounted in its reed block, the process is similar. To increase the tip clearance, rock the screwdriver tip down into the vent and against the tongue at a point about a third of the way up from the rivet. If you try to leave the leather on while you do this, you are likely to damage it, so I think you are better off to remove the leather to better see what you are doing, as well as to allow you to work from the fixed end of the reed tongue. Glue the leather (or a new one) back on when you are finished.

On larger reeds, you often must push the tongue so far in that it hits the back of its reed chamber and visibly bends to conform to the limits of the chamber. There is some risk that in addition to bending near the rivet, the tongue will bend in the opposite direction about where it contacts the back of the reed chamber. Such a bend puts undesirable curvature in the reed tongue, making it impossible to voice it correctly until it is straightened. If you are exerting force at about the 1/3 point, the reed tongue will nearly always reach its elastic limit near the rivet before it does in the area of the reverse bend, but not always.

The major exception is with some handmade reed sets in which a few of the largest treble bassoon reeds have a a very thin cross section near the rivet and a step up in thickness about half way out from the rivet. On those reeds, the tongue will reach its elastic limit and take a permanent bend near the rivet, but it is also likely to take a permanent bend in the reverse direction right at the step up in thickness, somewhere near the middle of the reed tongue. If this occurs, you will have to remove the reed from the reed block to straighten that tongue before you can voice it. To save wear and tear on the reed, it is best to remove this type of reed from the reed block before you try to increase the tip clearance of the inner tongue. Increase the clearance to match the clearance of its properly voiced twin on the opposite side of the reed plate, then wax it back in.

This Binci handmade reed has been flipped over to show what happened to the interior reed tongue when I tried to increase its tip clearance without removing the reed from the reed block. The reed would no longer sound until after I removed it, straightened it, properly voiced it, and waxed it back in.

To decrease the tip clearance of an interior reed tongue, you must push the tongue up into the vent. This is the trickiest scenario, because you must work through the hole in the bottom of the reed block, where it is hard to see exactly where your tool is contacting the reed tongue. In addition, the upward force you apply on the reed tongue might jack the reed plate right out of its wax mounting if you don't adequately support it. It is also harder to see and properly judge the amount of tip clearance and any impact you are having on it.

Start by laying your pry bar (narrow screwdriver) on the exterior face of the reed plate to measure how much of the shank you will want inside the reed block in order for the tip to contact the interior reed tongue at the desired point, i.e., 1/3 of the way from the rivet to the tip. Make some kind of mark on the shank, then insert it up to the mark and align it with the interior reed tongue. As you rock the handle downward, using the interior edge of the reed chamber as a fulcrum, the screwdriver tip and the reed tongue will rise into the vent. Be sure to have a firm grip on the reed plate, squeezing it onto the reed block to prevent the upward force of the tool from pushing the reed plate out of the wax. As always, be gentle at first. Rock the tongue a little ways up into the vent, then check the tip clearance to see if you have decreased it. You want to approach the elastic limit of the reed tongue gradually, so as not to significantly overshoot.

The goal is to have the minimum possible tip clearance that will not cause the reed to choke. Unfortunately, there is no way to know where the minimum is until you exceed it. Different reeds have different response times, even when properly voiced, so if you are really after the absolute best performance your reeds can deliver, you can’t simply stop when the response seems pretty good. Well, you can, and in fact that is almost certainly good enough, but who among us can stop there, if there may be some possibility of getting even better response?

To get the absolute best possible response, you need to find the point where the reed begins to choke, then widen the clearance the minimum amount to get it to not choke. If you are opening up the clearance on a reed that has already been choking, this just comes naturally. But if you are narrowing the clearance on a reed that has been responding too slowly, then you will have to keep narrowing it bit by bit until it begins to choke under sudden high pressure on your test bellows. Of course, that means you have gone too far, and will have to exceed the elastic limit one more time to put it right, but that’s okay, as long as you don’t do it too many times.

Voicing requires patience. After several failed attempts to change the tip clearance, frustration can cause you to suddenly get too rough with it and bend it too far. It is important to very gradually increase the force applied with each attempt, i.e., bend it just very slightly farther each time, until you just barely exceed the elastic limit. You will know you have barely exceeded the elastic limit when the reed tip returns to a slightly different clearance than before.

The optimum clearance is often about one reed tip thickness above the reed plate. However, this varies slightly from reed to reed, so simply measuring the clearance will not ensure optimum performance. You have to check it on your test bellows. Decrease the clearance a tiny bit at a time until you can just barely make the reed choke with a sudden onset of high bellows pressure on your test bellows, then back it off the minimum amount required to eliminate the choking.

You have to be especially careful when voicing the very smallest piccolo reeds, as they are very thin and bend readily (the smallest ones are only about .002" thick near the free end).The optimum tip clearance under the reed tongue is often too small to see without magnification (sometimes as little as .0015"), making the required changes likewise too small to see. In this case you will be unable to monitor your progress visually unless you remove the reed from the reed block and view it under moderately high magnification, say 10x to 20x. In the absence of such magnification, if you actually see a change in tip clearance, you have almost certainly gone too far. It is very easy to bend these tiny reeds too far, or to ruin them by putting a visible bend or kink near the tip of the reed tongue. You want the bend to be imperceptibly small, and located very near the fixed end of the reed tongue. It is best to remove these tiny reeds from the reed block, make your bends under magnificaiton so you can see your progress, test the voicing by placing the reed directly over the opening on the top of your test bellows, and wax the reed back into the reed block only after both its tongues have been properly voiced.

You should push on these tiny reed tongues only within the bottom half of their length, and gently. Use a wooden toothpick or a tiny screwdriver or similar tool, taking extreme care not to let it slip toward the free end of the reed tongue, or you may inadvertently bend just the tip, which will ruin the reed (unless you are patient enough and fortunate enough to be able to straighten it under magnification, as described on page "Accordion Repair 3" near the end of the tuning article).

When adjusting the tip downward, a good way to maintain control of your tool and of the pressure you apply is to rest the shank of your tool on the reed plate at the top (narrow) end of the reed vent, and rock the tip of your tool downward against the top of the reed tongue, forcing it down into the vent. This gives you precise control over how much pressure you apply, how far you deflect the reed tongue, and exactly where on the reed tongue you apply the pressure.

Similarly, when lifting the tongue, support it along more than half its length, rather than just pulling on the very tip. Slide a dull single edge razor blade or a .002" metal feeler gauge under the reed tongue to lift it. Be very careful not to bend it too far. If you actually feel it yield, then you almost certainly have gone too far and may have ruined the reed. It is best to begin with very light pressures and minimal deflections, checking each time on the test bellows to see if you have improved the voicing.